Emmanuel Carrère, The Art of Nonfiction No.5

The French, who are notoriously divided on literary matters, all seem to agree: there are few great writers in France today, and Emmanuel Carrère is one of them. Carrère writes nonfiction, or what he calls «nonfiction novels». His books combine journalistic reporting with first-person confession. «He transforms the world into literature», summarized one felled critic. He also shocks. In My Life as a Russian Novel (2007), he defied his mother’s request not to write about her father, a White Russian émigré who served as a translator for the German army during World War II. The French press delighted in the supposed rift it caused with his mother, a preeminent historian of twentieth-century Russia who happens to be the presiding secretary-general of the Académie française. In the same book, Carrère recounts the true story of how he surprised a girlfriend by publishing a pornographic letter to her in Le Monde. Though this marked the height of his take-no-prisoners exhibitionism, frankness about his worst self is a constant in his work.

Born in 1957, Carrère grew up comfortably in Paris, the son of an insurance executive. He attended the Institut d’études politiques de Paris (the renowned Sciences Po), and, after serving in the military in Indonesia, became a film critic for Télérama and Positif. He continues to work as a journalist, both in print and in television. (In addition to writing TV and movie screenplays, he has directed two films, including a documentary.) But Carrère’s narrator is not the neutral «I» of American New Journalism. He is unapologetically — or sometimes apologetically — present. For example, in his 2009 best seller, Lives Other Than My Own, Carrère tells the true story of his vacation in Sri Lanka during the 2004 tsunami. He then writes about the death, by cancer, of his girlfriend’s sister, who was a small-claims judge. Eventually, he goes on to explain French and European credit law, her field of expertise, in fifty pages that are, unlikely as it may seem, gripping. President Nicolas Sarkozy said the book «transforms the way you look at the world». (A tricky endorsement for the left-leaning Carrère.)

Carrère began his literary career writing fiction and looks upon his first, experimental novels with dismayed amusement. His first major critical success came in 1986, with The Mustache, a novella about a man who shaves his mustache only to find that no one notices, not even his wife. John Updike wrote that the book was, «to risk a rather devalued word, stunning». Carrère followed up with Hors d’atteinte? (1988), about an addicted gambler, and Class Trip (1995), about a killing by a pedophile. He also wrote a biography of the sci-fi master Philip K. Dick.

But the book that made him famous was The Adversary, published in 2000. It is justifiably considered the French In Cold Blood. The true story of a serial killer who murdered his family after pretending to be a doctor for eighteen years, The Adversary became a best seller and was translated into twenty-three languages. From that moment on, Carrère switched from fiction to his brand of first-person reporting. His most recent book, Limonov, won him the prestigious Prix Renaudot in 2011. Limonov will be published in English this fall.

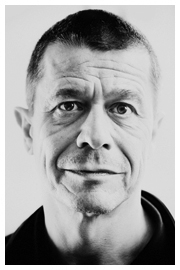

The interview took place in Carrère’s large, comfortable apartment in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. Slightly tan, Carrère looks like a French journalist, which means he can carry off a scarf and a vaguely fatigue-like jacket with panache. Despite his bohemian-bourgeois credentials, he has the courteous manners of his more conservative background. Listening to him is reminiscent of reading his books: there’s the intensity, which may strike the listener as somehow Russian, and the self-deprecating humor that can accompany the most embarrassing admission.

Carrère lives with his wife, Hélène Devynck, a former journalist, and their daughter. He has two grown sons from a previous marriage. He often writes at his house on the Greek isle of Patmos, where, he points out, Saint John wrote the Book of Revelation. He is currently at work on a collection of his long-form journalism, due out in France in January.

— I read that your editor made you entirely rewrite your first novel, L’amie du jaguar. Is that true?

— Yes, absolutely. I was extremely proud of the fact that I wrote it as a single three-hundred-page paragraph. I thought it was impossibly chic, an example of great literary radicalness. Instead of stopping me in my tracks by telling me that it wasn’t working at all, she just said that it was a little too long and overwrought and that I should try to make a few cuts, which I could put in brackets. I tried, but of course, it didn’t work, so I completely rewrote the book, which, I’m sure, is what she hoped I’d do. I think the book was promising enough to warrant a little tact, but really, it’s one of those typical first novels that are of interest only to their authors.

— You have said that the book is very autobiographical, which is something writers often deny completely.

— Yes, it was. It took place in Surabaya, in Indonesia, where I did my military service. It’s about a tortured young man who is in love and doing whatever drugs he can lay his hands on.

— It’s funny that the person who wrote this book, which is not realist at all, is the same person who wrote the nonfiction works that made him famous.

— It is both autobiographical and not at all realist, but I don’t find that combination to be so strange. There’s a book I really like called W, or the Memory of Childhood, by Georges Perec, which is made up of two completely different parts. On the one hand, he reconstitutes a novel he wrote as a child set on an island, Jules Verne–style, about a fascist society that is completely dominated by sports. On the other hand, he records his very fragmented memories of his life with his parents, from whom he was separated at the age of four when they were deported to the camps. And the way he uses these two stories — it’s as if he is trying to harness something he isn’t able to say. I have often used that method, combining things that don’t obviously go together and making the bet that, by doing that, I am going to access something that is in the realm of the unsayable. It’s something that works in psychoanalysis and I think in literature, too.

My publisher, P.O.L., recently reprinted L’amie du jaguar. I tried to read it, and I just couldn’t do it. When I wrote the book, I was crazy about Nabokov and, under his influence, I thought, Why make it simple when you can make it complicated?

— Your second novel, Bravoure, was inspired by a famous piece of literary history.

— What is true is that in the summer of 1816, Lord Byron, with his doctor, who was called Polidori, and the Shelleys — Percy and Mary — gathered in a house on Lake Geneva. This little group spent the summer together, going on walks, boating, and things like that but also reading fantastic fiction, which was just starting to be fashionable. They were quite obsessed with it, so they made a bet to see who could write the best horror story. Polidori’s story, which was called «The Vampyre», is the first vampire story in Western literature, outside of folktales. As for Mary Shelley, she had a nightmare, which produced Frankenstein, a book I adore. I love its naïveté, its tragic power. And I love the idea that this eternal story was invented by a girl of eighteen. And it is an eternal book. As long as we read books, we will read that.

— In the novel, you mention a writing exercise. Have you done it yourself ?

— It’s a piece of advice given by the German Romantic Ludwig Börne. «For three successive days, force yourself to write, without denaturalizing or hypocrisy, everything that crosses your mind. Write what you think of yourself, your wives, Goethe, the Turkish war, the Last Judgment, your superiors, and you will be stupefied to see how many new thoughts have poured forth. That is what constitutes the art of becoming an original writer in three days».

I continue to find this excellent advice. Today still, when I’m not working on anything, I’ll take a notebook, and for a few hours a day I’ll just write whatever comes, about my life, my wife, the elections, trying not to censor myself. That’s the real problem obviously — «without denaturalizing or hypocrisy». Without being afraid of what is shameful or what you consider uninteresting, not worthy of being written. It’s the same principle behind psychoanalysis. It’s just as hard to do and just as worth it, in my opinion. Everything you think is worth writing. Not necessarily worth keeping, but worth writing. And fundamentally, that’s what a large part of literature attempts to do — reproduce the flow of thought. Well at least the literature I love the most — Montaigne, Sterne, Diderot . . .

— Why is the book called Bravoure, which is sort of a cross between courage and chutzpah?

— Out of pretension, I’m afraid. There is an expression in French — «morceau de bravoure». It’s a novel that seeks to be virtuosic, to say, Look what I can do.

— But in the book, there is a moment when you use the word . . .

— To justify the title. Which is even more awkward! Can we move on?

— So you grew up in Paris?

— I’ve lived there my entire life, except for the two years I spent in Indonesia. I grew up in the 16th arrondissement in a bourgeois family. Until I was ten or so, I think I was a happy child, much beloved, possibly a little too cultivated, with glasses. I read enormously. I had a very pleasant childhood. Things went south at adolescence, which, in my case, started very early and ended very late!

— Tell me about your mother, who is a nationally important historian. She had a very difficult childhood.

— My mother came from the Russian aristocracy, but she grew up extremely poor. Her father disappeared when she was fifteen. Her mother died six years later, leaving her and her little brother in a very precarious situation. That’s when she met my father, who lived in Bordeaux and came from a family of musicians. My grandfather was a violinist. He was the director of Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux. My grandmother had begun a modest career as a pianist. Not so modest, actually, since, for example, Claude Debussy dedicated a piece to her. My father could have become a pianist, but his parents thought that social advancement required that he pursue something other than being an artist. So he went into the insurance business, while my mother became an academic who specialized in the Soviet Union.

— Your mother became a star.

— Yes. In 1978, she wrote a book about Muslims in the Soviet Union that was full of statistics and maps that predicted the demise of the empire, and, bizarrely, it became a best seller. All of a sudden, she went from being a respected academic to a kind of oracle on all Russian and Soviet questions.

— And how did you react to that?

— I was very proud of her, of course, but it also wasn’t easy, because the moment she became famous coincided with the moment I was starting to write. I had become the son of Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, and so to minimize that, I dropped the «d’Encausse».

— Were you aware of your mother writing?

— When I was little, yes. My mother is a woman with an insane amount of energy. She is eighty-four years old now, and if I took on a quarter of what she does, I would be wiped out in a week. She just doesn’t stop. She will go to Japan for twenty-four hours. And she was an extremely present mother. She worked very early in the morning before my sisters and I started making noise and running around. We didn’t even go to the school cafeteria. We came home for lunch!

— You finally had your own success with your novella The Mustache in 1986.

— I wrote that very quickly — in three weeks, including revisions. My major influence was no longer Nabokov, thank God, but something not quite as grand — the slightly paranoid sci-fi of the fifties. When the book came out, the critics kept talking about Kafka, because they always talk about Kafka when a story is at all odd, but really my models were Theodore Sturgeon, Richard Matheson, Philip K. Dick, or TV series like The Twilight Zone. I loved that stuff. One day, I got an idea for a short story in that genre — a guy shaves his mustache, nobody notices, and his life turns into a nightmare.

— What prompted the idea?

— People have often asked me that, and for the longest time I said I didn’t know. I was sincere. All I could say was, it just came to me. But then twenty years later, when I was doing research for My Life as a Russian Novel, the book about my maternal family I had had such a hard time writing, my mother told me a story about her father. As I told you, he disappeared. It happened in Bordeaux in 1944, and the truth is he was probably executed without a trial because he was a collaborator. He wasn’t a big collaborator, but still, he worked as a translator for the German police. During the liberation, he hid for a while. The last time my mother saw him, she felt profoundly disturbed, and at first she couldn’t figure out why. And then she realized he had shaved his mustache. She had always known him with a mustache, and all of a sudden to see him without one was incredibly unnerving. It was as if he had become an alien.

When my mother told me this, I was completely flabbergasted. I said to her, «Doesn’t that remind you of something?» She said, «No, what?» «My book La moustache!» And she looked at me with deep dismay and said, «You’ve done too much psychoanalysis».

— So the novel came easily.

— Without the slightest effort at all, curiously, given that it is a pretty horrifying story, so much so that the young woman who was editing it at P.O.L. refused to reread the last few pages. Whereas I wrote them in a kind of fit of jubilation. When I started, I thought it would just be twenty pages, but I had them done after writing for a day, and it was only the first day of the story. The story takes place over two weeks, and it took me two weeks to write it. Every day I wrote a day in the life of the character without knowing what would happen next. I’d go to bed thinking, We’ll see what happens tomorrow. It was completely improvised, and I was surprised until the very end.

— The book was a big success. How did you react to that?

— I could finally say to myself, Now I’m a writer, which had a perverse effect, although I only realized it later. Until then, I had been a journalist, a movie critic for Télérama, one of the most influential cultural magazines in France. It was the golden age of journalism — there was money. In addition to film criticism, I wrote on all kinds of subjects. I even did a three-month trip around the world, filing articles from a different spot each week. It was pretty fun. So, professionally, I saw myself as a journalist who aspired to write novels, who was able to publish a couple, who had a few kind reviews, but it wasn’t enough to make a living. And all of a sudden, here comes the third one, which makes money, is translated into eleven languages, and is praised by John Updike in The New Yorker. Even movie people were interested. I said to myself, This is my job now, I’m a writer, and that means I have to write regularly and not just when I feel like it, and I have to come up with projects. That’s the spirit in which I wrote my next novel, Hors d’atteinte?, which is a book I really don’t like. It’s workmanlike, it’s competent and serious, but I think I prefer incompetence and frivolity to that kind of competence and seriousness. I’d rather do anything else but write a book like that every two years.

— How did you come up with this story about a woman who becomes a compulsive gambler?

— At the time, I was seeing this young woman, and one day we were in Deauville and we pushed through the doors of the casino. I had never been to a casino and neither had she. Fundamentally, I wasn’t very interested in it. But she, on the other hand — I could see immediately that she could become a gambling addict from one day to the next. She was absolutely riveted by what was going on at the roulette table. I was right next to her, but she didn’t see me anymore. I could feel this void opening. It was as if someone who had never taken heroin did one day and suddenly it was obvious that this is what they liked in life — that and nothing else. It was this idea that in an instant a life can be upended, all bearings lost.

That notion was mixed up with another feeling I was having at the time, which I gave my heroine. Whatever choices I made, they ended up being those of my age group, of my social class. Every time I tried to be different or original, it only threw me deeper into that common lot, that sociological prison. Today, I couldn’t care less and even find it amusing. But at the time, it depressed me. And the other thing that didn’t help was that I was constantly reading and rereading Flaubert, who is the great poet of this kind of leveling.

God knows I love Flaubert, but I had to finally accept that whenever I’ve reread him, it’s been a terrible influence. I love his sentences, I love Madame Bovary, but I don’t like the kind of withdrawal he inspires in me. And all the little Flauberts who think it’s enough to have a kind of facile pessimism which passes for lucidity . . .

— That’s a caricature of French literature — you’re sad and then you kill yourself.

— Yes, exactly. I find that kind of smug pessimism, which says life sucks, morally offensive.

— After Hors d’atteinte?, you wrote a biography of Philip K. Dick.

— Hors d’atteinte? so did me in that I was completely blocked for the next few years. I made my living writing screenplays. At one point, my agent François Samuelson said to me, You know, the last recourse for writer’s block is biography. So I thought about it and immediately Dick came to mind. There was also something else, which was that, in the spring of ’90, I had done an article on Romania just after the fall of Ceaușescu. And Romania after the fall of Ceaușescu was one of the most terrifying places I’d been on this earth. It was The Twilight Zone. Everything felt booby-trapped and treacherous.

I remember one night in Bucharest. The government that succeeded Ceaușescu brought in twenty thousand miners who beat the crowds with crowbars. Unimaginable violence. I had become buddies with an American journalist who really got the crap beat out of him. We were drinking at the bar and we realized that we were both fans of Dick and that, in the terrifying chaos of Romania, we were constantly thinking of his novels, as if they were the only key to understanding anything about this incomprehensible world. So I came back convinced that writing a biography of Dick was the thing to do. I was also in a depression that I wasn’t really admitting to myself. I started psychoanalysis, which lasted almost ten years.

In the end, writing the biography was an excellent solution. It was like building a plane, with lots of pieces that you have to screw on tightly. I really enjoyed the construction game. And I liked to imagine Dick looking over my shoulder. In many respects, Dick was an insufferable guy, but during the two years I spent writing his life story, I never stopped feeling affection, even tenderness, toward him. We were good together.

— What attracted you so much to Dick?

— For me, he’s the Dostoyevsky of the twentieth century, the guy who understood it all. Actually, I am struck by his posthumous life — not only all the movies based on his books, but all the movies that aren’t, like The Matrix, The Truman Show, and Inception, that show reality disappearing behind its representation. It used to bother me that all these people didn’t admit their debt to Dick. But in the end, I think it’s great. What twenty years ago we called the world of Philip K. Dick is now just the world. We don’t need to cite him anymore. He’s won.

— Did you do lots of research?

— To be honest, no. I reread all his books in order. I read an excellent biography that already existed, by Lawrence Sutin. From that, I drew up a list of facts — when he got married, when he moved, et cetera. Then I threw the biography in the garbage so I wouldn’t be tempted to go back to it. Then I put the events of his life and his works side by side, betting that his stories, which appear to come from the most unbridled imagination, were, in fact, a form of autobiography. And it worked out pretty well. I went as far as using a conversation between two robots from one of the novels as dialogue between Dick and one of his wives. The result is a kind of journey through his brain. For the Anglo-Saxon reader who is used to very factual biographies, it must be bizarre. But it’s a book I’m fond of. Its fault may be that there’s too much information, making it exhausting for the reader. I believe in placing demands on one’s readers, but at the same time, you have to take care of them.

— Actually, you have a very conversational, natural way of writing. Do you edit a lot?

— A lot. What I’m looking for is a balance between a natural tone — intimate, conversational, as you say — and the maximum amount of tension, so that I can keep the reader engaged. Sentences need to have electrical current. There has to be both tautness and flexibility, speed and slowness, as in martial arts, which I have done a lot of. You have to simplify sentences as much as possible while making them take on more and more complex subject matter. I like what Hemingway says — Like everyone, I know some big words, but I try my damndest not to use them.

— Then you wrote The Adversary, your nonfiction book about Jean-Claude Romand, who killed his wife, children, and parents after pretending to be a doctor for eighteen years. Had you read In Cold Blood?

— Of course. I read it four or five times. Each time I was more impressed by the power of its construction and the purity of the prose. It’s a masterpiece. And of course, when you decide to write a book on a crime, it’s a shadow that weighs heavily on you.

— What drew you to the Romand story, apart from its extraordinary nature?

— I read about it in the French newspapers in 1993, when I was just finishing the Dick biography. And immediately I said to myself, I want to do something on this. I wasn’t the only one. It’s a story that fascinated an enormous number of people. It is an extraordinary case, unlike the one In Cold Blood is based on, which is fundamentally banal — a random murder committed by two little shits. When I attended Romand’s trial, every crime reporter in France was there, and they all said, A case like this, you encounter once or twice in a lifetime. The complexity of it, the horror, the tragedy. It touches on the abyss. So I wanted to do something, but I had no idea how to go about it. There are two ways to approach writing about a true story. Either you just let yourself be inspired and write a novel. In other words, you write exactly what you want — that’s apparently how Madame Bovary and The Red and the Black were written. Or there’s the In Cold Blood option — you really tell the story, and in that case, you’re not allowed to invent. It’s clear. You have to be on one side or the other.

But I didn’t know what to do. Finally, I wrote to Jean-Claude Romand, thinking, That will decide it. If he answers me, that will lead me who knows where, but forget fiction. Otherwise, I’ll figure it out on my own. Well, he didn’t answer. I tried his lawyer, who wouldn’t give me the time of day. So I considered that route closed. I started to write a novel, which brings us to Class Trip, which is, in an odd way, the fictional version of this story. Even if it doesn’t look like it, the novel deals with the same themes and the figure of the homicidal father harboring an unspeakable secret. The Adversary and Class Trip are twin books, made from blankness, silence, weeping that you can’t help but hear. They were very hard to write, and, I think, hard to read, too.

While I was thinking about the Romand story, I read about another case, unfortunately not uncommon, about a guy who raped and killed several children. In one article about it, there was a brief mention of his own children. It didn’t say much, just that this child murderer had children. And I remember being transfixed by this idea. I couldn’t stop thinking about those kids, what had been and what would be their lives. As if their fate was almost worse than the fate of the assassinated children. I know you aren’t allowed to say that, but all the more reason, it seemed to me, that I had to be the one to say it, that it was up to me, in my books, to take care of those children.

Of the five works of fiction I have written, there are two I really think are good — Class Trip and The Mustache. They are similar in the sense that there are short and tightly written, very straightforward in their narration, and that they were written in the same way — very quickly, without an outline, despite the fact that their construction is actually quite sophisticated. There are things on, say, page 20 that foreshadow things on page 80. But it wasn’t planned. It just came like that, straight from the unconscious, without premeditation.

— So what brought you back to The Adversary?

— After Class Trip was published, I received a letter from Romand, two and a half years after I sent him mine. He had read the book. He said he was devastated by it, that it reminded him of his own childhood, which didn’t surprise me. If I was still interested in meeting him, he was game. It was one of the most terrifying letters I have ever received. Still, we started a correspondence. I went to his trial as a journalist. I went to see him in prison. They were pretty strange encounters. Lots of small talk, oddly enough.

I spent the next five years trying to write the thing. I was buried under an enormous mass of information. The pièce de résistance is the official evidence file. It’s an incredible mixture of everything — testimony from witnesses, ballistic experts, and psychiatrists, miles of bank statements. I felt like a sculptor in front of a block of marble who thinks that somewhere inside it is a horse or a bust of a Roman general. From these hundred thousand pages, I had to produce three hundred and only I could write them. But how? From what point of view? From whose point of view?

What surprises me looking back is that it never occurred to me write the book in the first person. Truman Capote’s model was Flaubert. Flaubert’s idea was to write a book in the third person, entirely impersonal in the sense that the author is present everywhere and nowhere, and his personal involvement is nil. Which in the case of In Cold Blood is a complete lie. The book, which is a masterpiece, rests on a lie by omission that seems to me morally hideous. The whole last part of the book is about the years the two criminals spent in prison, and during those years, the one main person in their lives was Capote. Nevertheless, he erased himself from the book. And he did so for a simple reason, which was that what he had to say was completely unsayable — he had developed a friendship with the two men. He spent his time telling them that he was going to get them the best lawyers, that he was working to get them a stay of execution, when in fact he was lighting candles in the church in the hopes that they would be hanged because he knew that was the only satisfactory ending to his book. It’s a level of moral discomfort almost without equal in literature, and I don’t think it is too psychologically farfetched to say that the reason he never really wrote much else is related to the monstrous and justified guilt that his masterpiece inspired in him. But maybe my saying that shows my overscrupulousness. I don’t behave especially well, but I am a very moral person.

— And that’s what bothered you?

— Of course. How can you not say to yourself, What right do I have to write this? If you’re a lawyer or a judge or a court psychiatrist, you have a legitimate reason. Society is asking you to do it. But if you are the one giving yourself permission, by virtue of your curiosity or some cord it strikes in you, it becomes much more problematic. Here I come, out of the blue. Nobody asked me anything. What right do I have to judge Jean-Claude Romand? There was that, and then there was the other more personal reaction. I spent the whole time asking myself, What kind of filthy, distorted mind must I have to feel such a connection to this story? To be this obsessed with it must mean that deep down I somehow resemble Romand! I was ashamed in front of my children. I had the impression that I was revealing something inside me that was totally obscene and disgusting. At the same time, I couldn’t stop myself.

— So you tried writing the book in the third person.

— Yes. I tried to do it the way Capote did it, from different points of view. No other book of mine has had so many drafts, so many dead ends pursued.

After six years, I decided to give up. I tried to convince myself it was better that way. Good riddance. Now I can move on to other things. But I thought, Since I spent six years of my life circling this story like a hyena, I’m at least going to write a little memo about it all, just for me, to close the chapter, to remind me later what I endured all those years. I put away my thousands of printed pages and went back to my old diaries, and that’s how I wrote what was to become, though I didn’t know it at the time, the beginning of The Adversary. I think those first few sentences are some of the best I have ever written, and they mark my exit from my writer’s adolescence, which was steeped in influences and inhibitions. It’s the first time you hear my adult voice. «On the Saturday morning of January 9, 1993, while Jean-Claude Romand was killing his wife and children, I was with mine in a parent-teacher meeting at the school attended by Gabriel, our eldest son. He was five years old, the same age as Antoine Romand. Then we went to have lunch with my parents, as Jean-Claude Romand did with his, whom he killed after their meal».

I’m not an idiot. I very quickly realized that this impossible book to write was now becoming possible, that it was practically writing itself, now that I had accepted writing it in the first person. I wouldn’t say it was pleasant — but almost easy? Yes. Up until that point, I had a vague hostility toward the first person. But the moment I agreed to use it, something flipped inside me and opened up the path that I am still on to this day.

— Why is «I» such a relief to use compared to the third person?

— Because the third person was no one but appeared to give what was written the status of truth. And I didn’t think you could know the truth about Romand. On the other hand, I could tell the truth about myself in relation to Romand. You can be less than lucid, you can lie to yourself, you can be toyed with by your unconscious. Nonetheless, you have access to yourself. Others are a black box, especially someone as enigmatic as Romand. I understood that the only way to approach it was to consent to go into the only black box I do have access to, which is me.

— What did Romand think of the book?

— I gave it to him to read before it was published, but I said to him, It’s done. I won’t change a thing, whatever you say. Even if you tell me that I am wrong because your car was actually blue, not green, I won’t correct it. I prefer to take responsibility for my own mistakes than take on your reality. I don’t acknowledge the right to speak in your place. That is what I am proud of in the book, from a moral standpoint. I never spoke for him. I never put myself in his place.

A little girl once said something in front of me that I just loved. She had misbehaved and her mother was scolding her, saying, But put yourself in other people’s position! And the little girl answered, But if I put myself in their position, where do they go? I have often thought of that since I started writing these kinds of «nonfiction» books, the rules and moral imperatives of which I was starting to become acquainted with. I don’t think you can put yourself in other people’s positions. Nor should you. All you can do is occupy your own, as fully as possible, and say that you are trying to imagine what it’s like to be someone else, but say it’s you who’s imagining it, and that’s all.

— So what did Romand say?

— I went to see him in prison, two weeks after I sent him the proofs. It was Christmas Eve. I kept thinking we were obviously going to have some kind of Dostoyevskian scene. He’s going to insult me, or he’s going to start weeping or fall into my arms. It’s going to be absolutely devastating or very embarrassing. Not at all. During the two hours in the visiting room — when prison visiting hours are two hours long, you feel obligated to stay for the whole thing — he spent fifteen minutes giving me very prim compliments, telling me with extreme politeness that there were things he didn’t agree with but that on the whole, he thought the book was very good, which he said didn’t surprise him because he held me in such high esteem. And then he just went on to talk about the movies he’d seen on Canal Plus, and the Japanese-language class he was taking. Small talk.

— Seven years elapsed before the publication of your next book, My Life as a Russian Novel.

— It did. After The Adversary, I was completely psychically empty. To change things around, I wanted to do some reporting. And that’s how I ended up going to Russia, not knowing it was going to turn my life upside down.

— You were sent by the French TV news show Envoyé spécial, which is a little bit like 60 Minutes. What was the assignment?

— In the summer of 2000, they found a seventy-five-year-old Hungarian man in a psychiatric hospital in a small Russian town called Kotelnich, five hundred miles east of Moscow. It appeared that he had been there since 1944. He was a prisoner of war who had been captured by the Red Army. In the great chaos of Europe at the end of the war, he was moved from prisoner camp to prisoner camp until they threw him in this mental asylum, where he remained for fifty-three years. Nobody in the hospital spoke Hungarian. He himself didn’t learn Russian, which suggests a psychiatric ward may have been the appropriate place for him! He stayed there, like a lost piece of luggage or a kind of Kaspar Hauser. And then one day, a guy came to visit the hospital, and he did what should havebeen done fifty years ago — he called the Hungarian consulate. The man was repatriated, and it was presented as the return of the war’s last prisoner of war.

So I went to report on this, on not only his return but on the asylum in this little Russian town and its inhabitants. The trip was overwhelming for me. First of all, there was the fact of returning to Russia, where I had only been once with my mother, when I was little. And I was deeply disturbed by the story of this Hungarian man. At a certain point, I realized that there were echoes of the story of my maternal grandfather, who also disappeared at the end of World War II and who is certainly dead.

— There is no documentation?

— No, he simply disappeared. My mother was fifteen at the time, my uncle eight. They endured one the most difficult things there is. A disappearance isn’t like a death. You spend your time saying to yourself, One day, he’ll come back. You wonder, Where does he live? What’s become of him? Is he suffering? A missing person is a ghost. And I think my whole life has been marked by this ghost. All the more so because we didn’t talk about it. There was silence and shame because he had disappeared as a result of being a collaborator, because he was on the wrong side.

— He came from Georgian aristocracy.

— Yes, he was a very intelligent man, very cultured, who spoke many languages, but he was never able to integrate in France. He became a taxi driver, and he was very bitter. After World War I, he studied in Germany. Things had gone so badly in France that I can understand, without approving, the circumstances that made him like the Germans.

So here was this family ghost. And all of a sudden I was confronted by this other ghost, this other example of the living dead returning from the middle of nowhere. The town of Kotelnich became for me, in some fantastical sense, the place you go when you disappear. In the Tibetan Book of the Dead, they call that place the bardo. And the setting was perfect. A lost town in the Russian provinces in the year 2000 is certainly one of the most sinister places that exists on the planet. That’s how I got the idea, without being conscious of the stakes, of returning to Kotelnich after my assignment. Since the idea of a book was frightening, I said to myself, Let’s make a film. Obviously it’s not so easy to convince a producer to finance your project when you don’t have a script and all you can say to them is, I want to make a film about Kotelnich, of all places. But I managed to find one, and I installed myself with a film crew of three in Kotelnich for a month and a half. We started to film stuff that happened, which wasn’t much — scenes of daily life, monologues by the local drunks, the comings and goings of trains. The more days went by, the more I thought I was totally screwed and that there wouldn’t be a film at the end. I had this vague notion that I could start with the story of the Hungarian and end up with the one about my grandfather, but I had no idea how to go about it.

We returned to France, tails between our legs. I spent many anxious hours in the editing room with miles of uninspiring footage. And then something horrible happened, and the most horrible thing about it was that it ended up saving the film. During filming, I had met a young woman named Anya who was the girlfriend of the local FSB officer. The FSB is the successor to the KGB. She was a strange girl, charming, a bit of a pathological liar, who spoke French, was a great singer, and she liked us, unlike most of the people there, who were suspicious of us. She loved the fact that we were French, and she did a little work as a translator for us. Basically, she was our best friend there. Anyway, I found out three months after filming that she had been assassinated in the most brutal way, chopped to pieces by a lunatic with an ax. She and her eight-month-old child.

So we returned to Kotelnich, for the fortieth day of mourning. That’s the day, according to Orthodox tradition, that the soul leaves the earth for heaven. We filmed everything that happened over the course of the wake, which lasted four or five days. Except for the cameraman, who kept discreetly emptying glasses of vodka into the potted plants, we were drunk from morning until night — Anya’s mother, the FSB guy, our interpreter, everyone. There was no other way to do it. We barely slept. The emotional intensity of it all was insane to the point that if I didn’t have the film as proof, I would remember it as a dream. A fever dream, like in Dostoyevsky.

— How did the film lead to the book?

— While all this was happening, I took up Russian again. For the first time in my life, I kept a personal diary, but in Russian. Strangely, the fact of doing it in Russian, in this language that I didn’t really speak, made it much more intimate, as if I were able to write things that I wouldn’t have been able to in French. It was a bizarre mixture of a film-shoot log, childhood memories, dreams, and a reconstitution of my family history. And onto all of this was grafted another thing, which was my love affair at the time.

I had met a woman with whom I was madly in love. It was a very, very passionate relationship that subsequently was very unhappy for reasons I explain in the book. Right before the filming in Kotelnich, the newspaper Le Monde asked a bunch of writers to write short stories with the theme «travel». I didn’t really have any ideas, but then suddenly one came to me. I wrote a kind of pornographic story that consisted of giving very precise sexual instructions to a real woman, the woman I was seeing, on the train trip I knew she was taking the day the story was going to be published in the paper. Essentially, I was writing her a pornographic letter that was also going to be read by six hundred thousand readers of Le Monde.

When I think about it now, I am completely appalled. The strange part is that I actually thought it was a charming, innocent gesture that she would take as a declaration of love, a marvelous gift. Le Monde was submerged with hate mail, readers asking for their subscriptions to be canceled. It was a terrible scandal. Things, of course, didn’t at all go as I had planned. The effect on our relationship was catastrophic in a way I hadn’t anticipated. And all this happened between the filming in Kotelnich and Anya’s death.

— It really is a Russian novel.

— I went into a kind of depression that I came out of with the idea of writing a book that recounted, without making anything up, everything that happened during that crazy year of 2002 — in other words, the making of the film, Anya’s murder, the research I’d done on my grandfather, and the story in Le Monde and the disaster it unleashed.

The story in Le Monde was pure madness. But I don’t think any writer would have been able to resist the temptation to write about it. The strange thing was to shove that story in with all the Russian stories. I could have written two different books, but no, I always thought I had to tell it all together.

— Almost as if you had to show something about yourself to be worthy of writing about the other horror stories.

— Precisely. In the film and the book, there is a very important character, Sasha, the FSB officer who was Anya’s boyfriend. He was a mysterious guy, not without charm, handsome, with whom we had a curious relationship because he was alternately very friendly and completely paranoid. Part of his job was to keep an eye on us, but he would do it by getting drunk with us and telling us the most intimate details of his personal life. We liked him, but we were wary of him just as he was of us. At one point in the movie, after Anya’s death, he’s with me and we are both drunk and he says with sudden lucidity, «Go ahead. Make the movie. You have my permission. I only ask one thing, that it be delicate and decent». And I answer drunkenly, «Yeah!» I made the promise. Then a year later, I came back to show him the film. I can tell you, I was very anxious. Sasha watched the film attentively, and when we got to the part I just described, he put his hand on my arm and he said, «You kept your promise». I was hugely relieved. Then he added something that killed me. «You know what I like about it? You didn’t just come to take our unhappiness. You brought your own». That made me cry. I could have kissed him.

My Life as a Russian Novel was written in a state of total disarray, as if it were the last thing I was going to write. There’s a consequence-be-damned aspect to it that explains the book’s lack of discretion. I consider it an essential rule not to write things that would cause real people to suffer, and I completely transgressed it. I wrote things that made the woman I loved suffer and things that made my mother suffer, because she didn’t want me to write about her father. I did something I morally disapprove of, but honestly, I don’t regret doing it. At that moment in my life, it was vital that I do it, that I dare to transgress in that way. Still, I wouldn’t ever like to do anything like that again.

— How do you compare what you do to the currently popular form of confessional literature, or «autofiction», as they call it in France?

— I am always a little surprised to see presented as a recent fashion something that strikes me as one of the oldest urges that can push a person to write. From the dawn of time, when writers have picked up their pens, it’s to describe something either that happened to them personally or to which they were witness. Or else it’s invention, which is what we call fiction, but I suspect that urge came later. Everyone is now convinced that it’s natural to write a novel, when it’s actually a historic, specialized form, like the tragedy in five acts or the sonnet. Not that I’m against the novel or think the novel is dead. Not at all. I love novels. I would be very happy to write one again one of these days. To tell the truth, if I refuse to put the label «novel» on what I do, it’s a little overscrupulous, because in France you can call just about anything a novel. But I would rather preserve the more restrictive meaning — a novel is fictional, with imaginary characters and events. If you ignore that criterion, then obviously, my books are novels. They are novelistic constructions in which I make use of all kinds of novelistic devices, in which I strive to constantly sustain the reader’s interest, to create fear, pity, identification, suspense, and the yearning to keep turning the pages. So everything you try to do in a novel, I try too, with the only difference being that it isn’t fiction.

Also, novels are judged on their credibility while nonfiction isn’t. The Adversary as fiction wouldn’t work. If I had made up the story and brought it to my editor, he would have said, Look, it’s a good idea but you have to make it more realistic. Lying for eighteen years without being caught by the French tax authorities? That’s impossible! I’m just pointing out the old cliché that reality is stranger than fiction, but like many clichés, it’s true. Now, does it change anything that what I am writing is true? Yes, I’m certain it does.

— As it says on the French jacket of your of your much lauded next book, Lives Other Than My Own, «It’s all true».

— Yes. During Christmas break in 2004, I went off to Sri Lanka with my new girlfriend, Hélène, her son, and one of mine. We were both on the rebound, both divorced, trying to do the blended-family thing, which wasn’t going particularly well. And then there was the tsunami. Nothing happened to us for the simple reason that our hotel was a hundred feet above sea level. The night before, I had considered moving to another hotel on the beach. If we hadn’t been too lazy to pack our bags, all four of us would be dead. Anyway, all the foreigners sought refuge at our hotel, and there were many who had lost wives, children, parents. We were at the epicenter of the catastrophe, on the raft of the Medusa, and we spent five days just trying to help out in any way we could. We grew especially close to a French couple whose four-year-old daughter, Juliette, had drowned. We went with them to every morgue on the coast looking for her body. We found ourselves confronted with this enormous suffering and forced into an intimacy of such violence, of the kind you rarely encounter in a lifetime. Your first impulse is to be terribly embarrassed by the other’s suffering, and you don’t know what to do, and then there’s the moment when you stop asking yourself questions and you just do what you have to do. When we got back to France, it never occurred to me that one day I would write about what we lived through there. The thought of it was inconceivable, obscene, even. What’s more, before the trip, Hélène and I had been on the verge of splitting, but the intensity of what we had experienced together led us instead to move into this very apartment, where we still live today.

On top of all this, a very short time later, Hélène’s sister, who was also called Juliette, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She was thirty-three years old. She had three little girls. She was a judge near Lyon. Of course I was sad that this young woman was dying, but the truth was, I barely knew her and I was more concerned about Hélène. I went with her to her sister’s bedside in the last few days of her life. Juliette died. The following day, just as we were getting ready to go back to Paris, we were told that a colleague of Juliette’s, who was also a judge, wanted to talk to her family. All we knew about him was that they were very good friends and had one other thing in common, which was that both had had cancer as teenagers. Juliette had partially lost the use of her legs — she was on crutches — and he had had a leg amputated. They were both handicapped judges.

So off I go with Hélène to see the one-legged judge, thinking, This is a bit of a chore. I’m the fifth wheel, the one no one really knows, who is awkwardly trying to fit in. Then this judge, Étienne, sits down in front of us and speaks without pausing for two hours. And what he says leaves me stunned. He talks about their friendship. He talks about their work together as judges in small-claims court, which he describes in unbelievably technical terms and is, against all odds, completely fascinating. He talks about their handicaps. And whatever he is talking about, he says things with an openness and a nerve that I find incredible. After it’s over, as we are leaving, he turns to me and says, What I just told you, I don’t know, maybe it’s for you.

So I think about it. And I say to myself, I’ve just gotten a commission. I’m going to accept. What that man told us over the course of two hours was what his life had taught him about sickness, friendship, love, family, the law, injustice, justice, poverty. If I am able to write something that can evoke the emotion I felt during those two hours of listening to him, it is simply impossible that it won’t be a fantastic book. And what’s more, he’s the one who asked me to do it!

— There’s a very funny passage when you tell your girlfriend you want to write about this and she says, Let me get this straight. You want to write a book about two lame judges who don’t sleep together and one of them dies?

— And the bonus is, they are experts in debtor-creditor law! What a pitch! It’s funny, I obviously didn’t write it for this reason, but I was always convinced that the book would be a triumph, that everyone would want to read it. I started working on it but then I stopped. I just couldn’t do it. Hélène was pregnant. I was afraid of having another child at my clearly more advanced age. I had this confused but very strong conviction that I had to do something decisive to free myself from neurosis. That’s how I ended up writing My Life as a Russian Novel. It was like leaving behind a giant load on the side of the road.

— Every book seems to be the result of failing to write another!

— Bizarrely, yes. You paint one coat, then you’re blocked. You go off to do something else and when you return to the abandoned work, you realize that over the course of the year, things have changed without your realizing. Something that was impossible becomes possible.

— How did you come back to the tsunami story?

— After My Life as a Russian Novel, I was feeling liberated and in no hurry to get back to work. I went off to the mountains for two weeks, and in the evening, after long hikes, I started writing in a notebook just what came to mind. Remember Ludwig Börne’s rule — write whatever crosses your mind for three days. And that’s how I suddenly found myself trying to gather my memories of the tsunami, despite having thought I wouldn’t write about it or even that I had forgotten it all. I reconstituted what happened those five days practically hour by hour. And then I just continued with the story of Étienne and Juliette as if it logically followed. The book wrote itself pretty easily.

— But why the two stories together?

— There is the accidental but essential link, which is me. I was witness to these two events in a period of a few months. They are two of the things that are the most terrifying in this world — the death of a child, for its parents, and the death of a young woman, for her children and husband. Freud said that the goal of psychoanalysis is to turn neurotic misery into ordinary misery. Lives Other Than My Own is entirely devoted to ordinary misery. Losing a child or your wife or getting caught in a tsunami — those are horrific events, but they are ordinary suffering. That’s life. From the moment you are alive, you are exposed to separation, mourning, death. In my case, I have incredibly been spared from that kind of pain. On the other hand, everything that is of the order of neurotic misery I know well. My Life as a Russian Novel is a kind of anthology of every kind of neurotic misery there is, whereas Lives Other Than My Own isn’t neurotic at all. Also, with the first, I had the impression that I was hurting people, that I was an asshole. With this book, not at all. I was writing it with the permission of the people it was about and even at their request. As painful as the book is, it was soothing to write.

— Is there anyone who didn’t like it?

— If so, they haven’t told me. The incredible consensual aspect of the book is a little embarrassing. I still get letters from people telling me that it changed their lives or helped them survive a period of mourning. It’s as if I’ve gone from deranged little pervert to the Mother Teresa of literature.

— Your own mother must have been pleased, after the trial of your Russian book.

— Yes. She said very sweetly, I’m pleased because I was under the impression that I must have been a monstrous mother to have created such a monstrous son.

— One thing that saves the book from corniness is the way you make fun of yourself. You’re very frank. For example, when you find out that Juliette is dying, your first thought is, I’m going to miss the opening of my film in Yokohama!

— It’s like when Étienne, the judge, says that the night before he had his leg amputated, he had sex with some guy in a sauna. I wrote it, but I said to him, We can cut this if you want. He has a family, he’s a heterosexual, a judge. It could have embarrassed him, but he said, No, you can keep it. I think that’s fantastic, and what’s more, he isn’t at all an exhibitionist. One of the things I find so lovely about him is that he knows where to place shame. There is so much stuff there is absolutely no need to be ashamed about, and yet so many people are ashamed. I think it’s good to just say those things, because it’s liberating for others. Many of the great writers I love — Montaigne, Dostoyevsky — endlessly do that, which is to say, I’m a human being and a human being does stuff like this.

— We come to your last book, Limonov, which is again nonfiction. Who is Limonov?

— Eduard Limonov is a Russian writer who is about seventy. I knew him in the eighties in Paris. The Soviet-era writers at the time were mostly dissidents with huge beards. Limonov was more of a punk. He was an underground prodigy under Brezhnev in Moscow. He had emigrated to the United States, been a bum and then a billionaire’s butler. He had a kind of Jack London life, which he wrote about in autobiographies that are actually very good, very simple and direct.

Then came the fall of the Soviet empire and things got strange. He went off to the Balkans and started fighting with the Serbs. He became a kind of crypto-fascist. It was a little like finding out a friend from high school had joined al-Qaeda. But time went by and I didn’t give it much thought. Then the journalist Anna Politkovskaya was assassinated, and I went to cover it. I was amazed to discover that in the little world of liberal democrats around Politkovskaya, Limonov was considered a fantastic guy. It was as if Bernard-Henri Lévy and Bernard Kouchner suddenly said, Marine Le Pen, now she’s great. I was so intrigued that, in 2007, I decided to go see Limonov. I spent two weeks with him trying to understand this strange political and personal trajectory.

— The mystery of fascism? Was that what intrigued you?

— I remember the exact moment I decided to go from reporting to writing a book. Limonov had spent three years in a labor camp in the Volga, a kind of model prison, very modern, which is shown to visitors as a shining example of how penitentiaries have improved in Russia. Limonov told me that the sinks were the same ones he had seen in a super-hip hotel in New York, designed by Philippe Starck. He said to me, Nobody in that prison could possibly know that hotel in New York. And none of the hotel’s clients could possibly have any idea what this prison was like. How many people in the world have had such radically different experiences? He was really proud of that, and I don’t blame him. My socioeconomic experience is relatively narrow. I went from an intellectual bourgeois family in the 16th arrondissement to become a bourgeois bohemian in the 10th. So these trajectories of the little boy in the African village who becomes the UN secretary-general or the little girl from east bumfuck in Russia who becomes an international supermodel fill me with wonder. I have to admire that amplitude of experience, the ability to integrate completely different values and ways of thinking. Limonov’s story, from that point of view, is fabulous. It’s a picaresque novel that also allowed me to cover fifty years of history, the end of the Soviet era, and the mess that followed. I’m surprised that the book has received the unanimously warm reception of the last one.

— Will you continue writing these, for lack of a better term, nonfiction novels?

— Yes. For the moment, that way of being present in the book but not its subject suits me. I feel more and more liberated. But I do have a vague idea of something I would like to do. It seems to me that my goal in life and in my work is to be able to access the first person, to be able to say «I», in a way that rings true. And now I’m starting to realize that it shouldn’t take up so much room, that that «I», which is so imperialistic, so anxious and overpowering, should recede and finally disappear. It would be worth it to hang around on this earth long enough to move forward on that path, if only just a little.

Susannah Hunnewell | «The Paris Review», No. 206, Fall 2013

copyleft 2012–2020

copyleft 2012–2020