edward limonov was born in Russia, lived in New York City in the 70s, and currently lives in Paris. He is the author of several novels, including «It's Me, Eddie», «My Butler's Tale», and «Memoirs of a Russian Punk».

manuel ramos otero, richard hell, kelvin christopher james, veronica vera, larry mitchell, jack henry abbott, willie colon, taxi with veronica vera, marc elovitz, anonymous, mike mcgonigal, george konrad, linda yablonsky, alfredo villanueva, christopher o'connell, grace paley, hubert selby, diviana ingravallo, herbert huncke, nick zedd, ameena meer, guy-mark foster, miguel barnet, edward limonov, adrienne tien, arthur nersesian, lynne tillman, darius james, david wojnarowicz, ed vega, kurt hollander

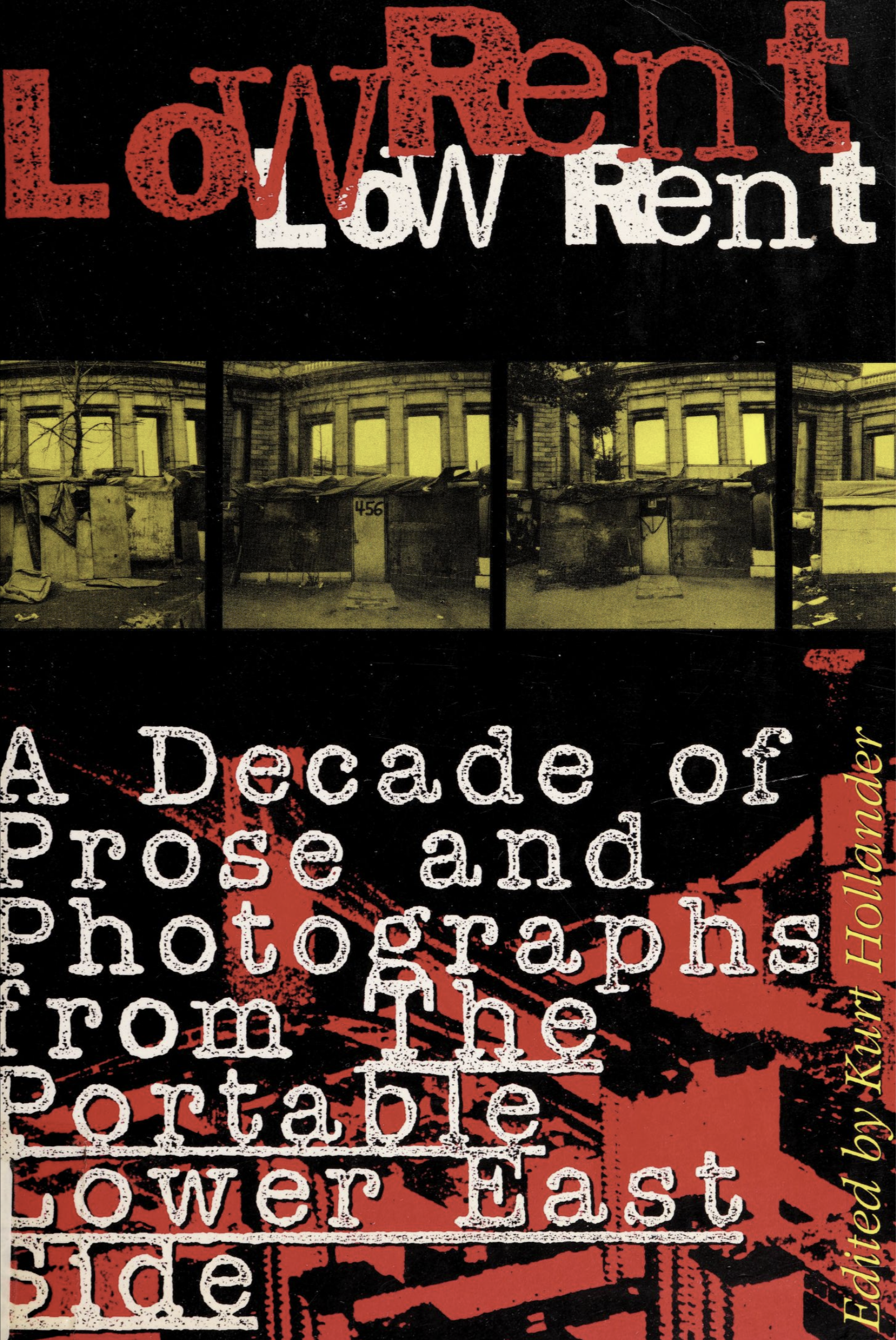

Low Rent:

a decade of prose and photographs from

the portable lower east side

/ edited and with an introduction by Kurt Hollander

// New York: «Grove Press», 1994,

paperback, 304 p. (XVI+288),

ISBN: 0-8021-3408-4, 978-0802134080,

dimensions: 235⨉152⨉32 mm

https://archive.org/details/lowrentdecadeofp0000holl/mode/2up

andy warhol's quarter

edward limonov

A cartoon character with moonlight hair was walking on Madison Avenue, a purple rucksack on his back. One might say Tintin on promenade. «Look, another Andy Warhol impersonator!» my friend said. We were coming from uptown.

«No,» I said, «that's him. Absolutely and positively him. I saw him a few times at Glickerman's parties.»

Tintin stopped at the intersection of 63rd Street and picked up the receiver from a street telephone, then started to look in his pockets for a dime. «Christ, he needs a dime. Jesus, Andy Warhol looking for a dime! Should I give him one?» my friend asked. «I have one.»

«If you wish,» I said.

He went up to Tintin and tapped him on the shoulder. «Andy,» he said. «Hey Andy, I have a dime!»

I didn't hear what Tintin responded. I was standing near the mailbox on the north side of 63rd Street, with the November wind blowing from uptown. I saw them fumbling with change.

My friend came back with an idiotic smile. «Ha,» he said, «he gave me a quarter.»

«You can be proud,» I said, «it's not easy to make a profit on Andy Warhol.»

«No profit. I gave him two dimes and five pennies. One at a time, with him waiting.»

«You gave it yourself, or did he ask for it?»

«He asked,» my friend said. «He's a fucking billionaire, but he patiently waited for fifteen cents.»

«That's why he is a billionaire. But tell me, why didn't you give him that miserable dime for free?»

«You see,» my friend said, «I wanted to get something from him as a memory.» He looked at the quarter in his palm.

«Scrape something on it,» I said, «so you won't mix it up with ordinary quarters.»

He took my proposition seriously and scraped the letter «W» on the face of George Washington with a key. «Unbelievable,» he said. «The boys in Kharkov wouldn't believe us. What a story! We're walking down Madison and Warhol himself, just like us also walking along, the most important genius of our time! And his sneakers aren't even Adidas, just some insignificant model, and that rucksack of his, polyester shit.» He grimaced in disgust.

«That's his principles,» I said.

«What do you mean by that?»

«He wears polyesters on principle. He worships nylon shirts and all those nonnatural products. He is the prophet of artificiality, the spiritual son of Picabia, moonlight Nazi Czech—The Killer of the old fat-assed culture. Waiting for fifteen cents is perfectly in accordance with his principles. Militantly anti-Romantic, he enjoys calculations and takes pleasure in talking about money.»

«How do you know all that?» my friend asked.

«Because I read, unlike you,» I said.

«I am an artist. I don't need books. Reading is important for writers.»

«So, run after him and kiss his ass. He also claims that he doesn't read books. But he wrote one. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. It so happens I learned English reading his book. Somebody gave it to me.»

«What's it about? Interesting?»

We had reached 57th Street and stopped indecisively on the corner. Actually, we had no plans and plenty of time ahead. He had lost his job as a photographer at the New York University Hospital the week before. I didn't have a job at all—I was on welfare.

«I should've asked him about a job,» my friend said. «He's from a family of emigrants, also. And Czech, you know, Slav. We have the same blood.»

«I thought you were Jewish. And anyway, Andy Warhol has no blood, he's electric. I'm sure if you part his hair you'll see the wires, microchips and all that.»

«Stop it,» he said. «Who are you to laugh at him? He is the Superstar, and you are zero, welfare recipient that you are.»

«It's still not night yet,» I said. «I am only thirty. I have time.»

«Sure you have.» Suddenly he looked very sad. «What are we gonna do?»

«Let's go to Central Park. We can buy some hotdogs and a small bottle of brandy. And I have a pint.»

«Again? Pleasures for the poor. We've gotten drunk in Central Park maybe a hundred times. Okay, let's go. What else can we do without money.»

We turned to the right.

«I wonder,» I said, «if he goes to Central Park sometimes? I mean Andy.»

«What for? He goes to the Plaza for champagne with Liza Minelli. Unemployed scum, like us, go to the parks, to sit and wait for nothing. Fuck, I wanna be rich! Riiich and famous!» he screamed. The passersby on 57th looked at us suspiciously.

«Why didn't you kidnap Andy Warhol on Madison,» I said. «You missed your chance, baby. It was easy to do. He was all alone, no bodyguards. Just snatch the genius and push him into the trunk of a car.»

«Do you think he's worth a lot?»

«You doubt it? You could also force him to work in captivity. He'd produce the pictures and you could sell them. You'd have no problems with him. He'd be a model prisoner. I read his book closely, word by word, using a dictionary. I know he doesn't need much, Andy. A tape recorder would be enough.»

«I'd feed him only Campbell's soup,» my friend smiled maliciously.

«He might hate Campbell's soup.»

«He'd eat it for the sake of his image. Also, I could use those photos of the corpses that I took for the hospital, you remember, I showed them to you. He could just drop some acrylic paint on them, a few drops here and there, and it would be worth tens of thousands! I'm sure I could produce better droppings myself, but his signature is important.»

«Yes, I know, you're a genius also,» I said.

He didn't respond to my sarcasm, he was following his own thoughts. «How do people manage to get so big, so symbolic, so unique, huh Edward? Fucking Czech. Did you notice, Edward, that they're ugly people, those Czechs?»

«Haven't seen many. Actually, I've known only one Czech woman, in Rome. She was hysterical, but rather of ordinary ugliness.»

The autumn leaves were scratching asphalt on 57th Street. The wind suddenly whirled them up and threw them into our faces.

«What fucking weather,» my friend said. «And he's walking around with only a light jacket on.»

«Who?»

«Warhol.»

«I told you, he's electric. And maybe his shirt is heated. He could easily put batteries in his rucksack and walk around as long as he wishes, you know, like he's wrapped in an electric blanket.»

«I have one at my place, stolen from the hospital of course. I was supposed to talk to him instead of counting pennies. Shit! I was supposed to ask him, «What's your secret?»»

«I can lend you his book. Apparently, as a boy he was sick and tired of all those Czechs around him talking a minority language, so he put all his strength together in order to get out. I believe that one day he got very angry, I mean seriously angry with the world. And that is the best thing that can happen to a man. Extremely rare as well, maybe nine in ten million might experience it. Then, angry as hell, you can get beyond the man. To get there once in life is enough, and you'll always remember that one time.»

«What's beyond?» my friend asked. «Does he say?»

«He didn't say. Actually, he didn't even mention that he went beyond. But I have a strong conviction that he did.»

«And what do you think is there?»

«Nothingness, I guess. Indifferent, non-hostile Nothingness. No need to worry, you just choose yourself as you wish to be. That's what Buddha discovered also. Another Superman, Buddha.»

«Do you think Warhol is as big as Buddha?» My friend became suddenly sad.

«That's a good question,» I laughed. «To put it shortly, our Czech discovered that if you don't help yourself, nobody is able to help you.»

«You're talking like Madame Margo, the reader and advisor who lives under my apartment. Are we going to the liquor store, or not?»

We bought a bottle of brandy and four hotdogs. We scrounged around for the pennies to pay for the hotdogs, but finally we were obliged to give up the struggle. The hotdog man, a Yugoslav, took Andy Warhol's quarter and put it in the pocket of his apron.

«Anyway, I couldn't possibly spare his coin for long,» my friend said when we placed ourselves on the bench. «That's against my principles.»